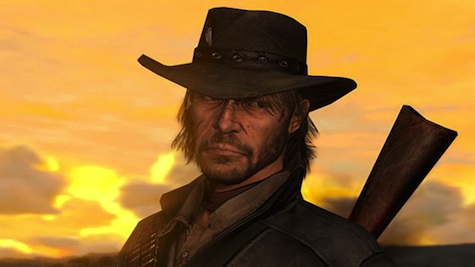

Just the other night I finally finished the 2010 open-world American frontier game Red Dead Redemption. Although tedious at times (HOW MANY TIMES DO I HAVE TO HELP YOU, DICKENS), the game did an amazing job of sucking me into the environment of the waning American frontier and I can absolutely see why it’s considered one of the best games out there.

The first thing I did after the credits rolled was probably the first thing a LOT of gamers did, I imagine: look up whether the game’s ending is unavoidable or whether we just did a really bad job in that final face-off. (Spoilers for the ending ahead, y’all.) What I found was surprising, although not in the way that I had hoped.

While searching for details regarding the game’s ending (It is indeed unavoidable, although if I really want to see John Marston again I’m told I should play Undead Nightmare) I came across a lot of posts on gaming forums complaining about how the ending sucked. This threw me completely for a loop.

Although Red Dead Redemption initially frames itself as a story about redemption and being able to forge your path through life anew, what it’s ultimately about is the close of the very era that produced frontier gunslingers like the protagonist, John Marston. In the game you, as Marston, are just trying to go straight and get your wife and kid back. (It’s very Thomas Jane of you.) But the larger conflicts that you become embroiled in are all about instituting widespread change. The year is 1911 and your mission is to hunt down a series of outlaws as an unwilling tool of the U.S. government reps newly arrived to the Texas border area that you live in. While being forced to institute order in the region, you also end up helping initiate the Mexican Revolution, which succeeds in changing the hands of power in that region. (There are also hints of a continent-spanning war brewing in Europe, although that particular shot is yet to be heard ’round the world.) Change is coming for everyone.

Even the secondary characters you meet along the way rarely make it to the end of the game, becoming lost in the wilderness of the west, succumbing to their own vices, or getting ground up in the battles across the region. They don’t belong in the future that is to come, but it’s all your character dreams about. So when you finally finish doing the government’s bidding and are back at home with your wife and kid, why doesn’t the game end?

Because John Marston is himself the last lingering thread in this story about a dying frontier. You get some nice days with your family, but it’s not long until the government arrives at your farm in force. You manage to save your wife and kid. But in a tense final stand-off against nearly 20 army rangers, you, the player, finally meet your end.

Although I hated not being able to survive this moment, to do so would have cheated me out of the satisfaction of the story’s conclusion. After the game had gone to such trouble to immerse me in a world that felt utterly real, having Marston survive such an impossible situation would have devalued my investment in its reality. This was always how the story was going to end. And it’s not like Red Dead Redemption hadn’t warned me time and time again.

To see others protesting this ending left me wondering—very much in a thinking-out-loud way—if the very concept of narrative, or cause and effect, is simply broken in maturing gamers who have spent their lives absorbing narrative as it is constructed through games. Stories are typically elusive in video games, and even games that attempt it (like RPGs or similar adventure stories) usually have to ignore their own world and their own rules from time to time just so the characters live to see the next scene. If you grow up with that and only that, does this kind of jagged, cheat-able style of narrative become your baseline for how you judge all stories? John Marston’s death violates a core expectation of video game narratives; that there’s always a way to win.

This kind of speculation pigeonholes young gamers though, and ignores my own main counter-argument to this, which is that I grew up playing video games, reading comic books, and watching blockbuster films, and I was able to learn how narratives work beyond those sources. My speculation doesn’t hold up long against this, but I can’t help but wonder if there’s that little sliver, that tiny percentage of gamers, whose understanding of stories becomes stunted by their immersion into video games.

There’s a more likely explanation for the anger that the ending produces, however, which is that Red Dead Redemption’s ending actually does its job too well. You spend a lot of time leading the main character John Marston through the world and the game is open-ended enough that you determine how his interactions play out. Either you’re a selfish monster or an honorable hero, and you can switch back and forth between the two whenever you like. By the end of the story, you as the gamer identify wholeheartedly with him because you essentially made him what he is through your own choices.

So when the unavoidable ending arrives, you feel a very real sense of loss. You failed. It’s the kind of emotional holy grail that video games strive for and rarely pull off. Red Dead Redemption does it, though, and I wonder if the anger at that ending—dismissing it as poorly done—is really just the kind of misplaced anger that one feels over having lost a loved one; when something is gone, when there’s really truly nothing to be done, and nothing to fix or direct your anger towards. Simply put…does Red Dead Redemption put gamers in mourning? If so, a gamer could certainly be forgiven for dismissing the ending, especially if he or she has never actually had to deal with loss in life.

Nothing’s ever simple, so I imagine the reaction to Red Dead’s ending consists of a bit of both. Plus a little outrage at being left with the less than ideal Jack Marston. (I mean…c’mon. Not even Anakin Skywalker liked Anakin Skywalker, you know?)

Personally, I think the ending to Red Dead Redemption is nearly perfect, but even I can’t completely accept it. I still like to imagine how the Marston family’s life would have played out had everyone lived. I can see Jack heading off to university as war rages in Europe. He’d be too old to be shipped out once the U.S. became involved in World War I, but maybe he’d be a war reporter, considering his love of adventure writing? If the Marstons get to keep their farm, then it would wax as the area became more developed, then wane as the area become over-developed. I’d like to think that the Marstons would do well during the Roaring 20s, not making too much of a fuss and enjoying the onset of modernity.

John and Abigail wouldn’t survive long through the Depression of the 30s, I imagine, but that seems all too appropriate. The United States after that is a shiny, hopeful, atomic thing and not really a fit place for a frontiersman who can’t drive. Perhaps it is best after all, that the sun set over Marston when it did….

Chris Lough is the production manager of Tor.com and if you liked this just wait for his think piece on the Bolshevik politics of Pac-Man.